This guest post is an excerpt from Darin Detwiler’s upcoming book, Food Safety: Past, Present, and Predictions, scheduled for publishing in June 2020.

One of the hottest topics at food industry events is technology. Any discussion of the food industry and technology inevitably includes a focus on data collection and analysis related to compliance and reputation. Some new technologies, or “RegTech”, are promised as key optimization tools—not only for addressing some of the industry’s key food safety challenges, but also for consumers as they “can now expect to see the entire histories of the products they buy to make more informed decisions.” Some in the food industry describe Blockchain using words such as transparency, traceability, network, partnership, and big data. Some retail giants use words such as “required.”

Walmart describes itself as “the world’s largest retailer” since having become “the masters of supply chain management.” The retail giant has “endeavored to become a leader in the area of implementing supply chain technologies to achieve the kind of operational efficiency that makes these cost savings possible.” In a September 24, 2018 press release, Walmart announced that they will require real-time, end-to-end food traceability from its suppliers of leafy green vegetables by September of 2019. Specifically, their suppliers must use IBM Blockchain technology.

Advance Your Regulatory Affairs Career

Learn how Northeastern’s Master of Science in Regulatory Affairs of Food program can prepare you to become an industry leader.

What is Blockchain?

Blockchain, as a form of regulatory technology, offers a decentralized e-ledger; a collection of blocks of information for each step, farm to fork. It lives in multiple locations at once, making it extremely difficult to edit, change, or forge. Being immutable, Blockchain creates a permanent record, which can be referenced quickly and with greater confidence than traditional records in the event of an emergency.

According to Walmart:

“Blockchain is a way to digitize data and share information in a complex network in a secure and trusted way. For food safety, this helps to more accurately pinpoint issues in the food chain and further protect customers against foodborne illnesses…For more than a year, Walmart, working with IBM and 11 other food companies, has successfully developed a Blockchain-enabled food traceability network built on open-source technology. In an initial pilot conducted by Walmart and IBM, the amount of time it took the retailer to trace an item from store to farm was reduced from seven days to just 2.2 seconds.”

According to IBM:

“Blockchain offers complete visibility of the data behind the many stages of product creation. Manufacturers, farmers, wholesalers, suppliers, delivery services and stores each input information that details and verifies their roles in the process—creating a log that provides irrefutable evidence of a product’s provenance.”

This imperative from Walmart is not the first time that retailers, including Walmart itself, served as the driving force for technology change in the food industry. This first step towards the types of today’s cutting-edge technologies can be found over 50 years ago in the development of barcodes found commonly on today’s food packaging and labels.

From Barcode to Blockchain

The Kroger Company, which runs the largest supermarket chain (by revenue) in North America, published a wish for a better future in a 1966 booklet, stating: “Just dreaming a little…could an optical scanner read the price and total the sale…Faster service, more productive service is needed desperately.” A few years later, grocery industry advisers searched for a solution to standardize the storing of a product’s pricing information. Their work came to fruition on June 26, 1974, when, at a supermarket in Troy, Ohio, a worker swiped a 10-pack of Wrigley Juicy Fruit gum—the first item scanned for its Universal Product Code (UPC). From that point on, the information in the hands of the giant retailers became as valuable as the products on their shelves. Their “control over information” is described as the “shift in Wal-Mart’s power.”

The goal of standardizing is not only to scale its common language on a barcode on an item that can be scanned anywhere in the world, but also to boost efficiency and profit at that retailer. To do this, the food industry, as well as the health, transport, and logistics sectors, have relied on GS1 US to manage the barcode standard used by retailers, manufacturers, and suppliers.

While barcodes are still used today, their format and how they are read has changed. In 2004, Wal-Mart announced that it would require suppliers to provide radio frequency identification (RFID) microchips by the end of 2006 to identify the item to which it was attached. This provided for more detailed inventory and supplier information than a bar code and increasing speed and efficiency of stocking and at checkout lines. The reality of Walmart’s experience with RFID technology, which should sound an alarm for any future technology, is that, according to Bill Hardgrave, former Walmart RFID technology consultant, “RFID technology… didn’t work that well. Despite the hype around Walmart’s pilot project, the tags were not giving suppliers useful data.”

Newer formats, such as those seen with the longer barcodes, came out of the work associated with the Produce Traceability Initiative (PTI)—a voluntary program for companies in the produce industry to maximize tracking and tracing efforts. With PTI, companies label cases with GS1-128 barcodes to significantly expedite outbreak investigations and recalls through globally unique identification of the brand owner of the product and other information, such as the batch/lot information. As of 2018, industry estimates of produce cases with PTI labels were at 60 percent, but these changes did not happen overnight. In 2010, the Produce Marketing Association and the United Fresh Produce Association conducted an industry survey about attitudes and implementation of traceability measures in which they polled more than 260 industry members selling in the U.S. While nearly 75 percent of produce companies polled indicated that they were working to implement the Produce Traceability Initiative at that time, the survey revealed a number of reasons preventing implementation. Similar to what is seen with Blockchain today, the top three obstacles to the implementation of PTI at that time were the perception of high costs, lack of awareness of the initiative, and waiting on government regulation.

Another change to barcodes is the use of Quick Response (QR) Codes—the square, matrix (or two-dimensional) machine-readable barcode labels that contain information about the item to which it is attached. Consistent in these changes are the increased amount of data that can be accessed from these codes and how it helps understand the products—in this case, food.

Barriers to Blockchain in the Food Industry

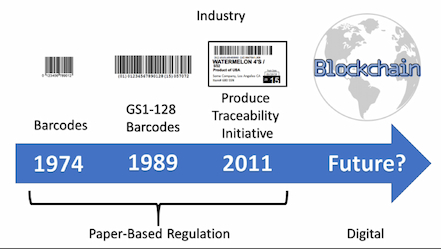

When the food industry agreed to adopt barcodes and supported the launch of the first GS1 barcode in the 1970s, federal and international regulators only had a paper-based requirement for proof of production, sales, and distribution.

After the introduction of barcodes, the GS1-128 code and the Produce Traceability Initiative moved the industry forward to relay more information from the farm to retailers and even to consumers. However, according to Northeastern University College of Professional Studies Regulatory Affairs of Food alumnus Nathan Libbey, “regulators still remained static in their requirement and suggestion of a paper standard for one-up-one down traceability and accountability.”

Figure based on a presentation by Nathan Libbey, 2018.

Even with the 2011 FDA Food Safety Modernization Act (FSMA) that had effective implementation dates of 2016 to 2018, paper was the standard for records. Only recently has the industry seen a change in the government’s stance on the digitization of records.

FDA Commissioner Scott Gottlieb, after multiple outbreaks tied to Romaine lettuce and other leafy green vegetables in 2018, issued a statement in which he declared that “Complicating this already large-scale investigation, the majority of the records collected in this investigation were either paper or handwritten.” Thus, the FDA’s emphasis on industry work to standardize record keeping and adopt traceability best practices now includes the use of state-of-the-art technologies. But this was only a suggestion from the U.S. government.

Changes in Perceptions of Blockchain for Food Safety

The food industry perceives that Blockchain (or some other form of an accessible, cloud-based method of storing and tracking data from transaction to transaction throughout the entire chain) is the next step in the evolution of quality assurance, regulatory compliance, and traceability technology. Outside of a dozen or so companies working directly with Walmart, most of the U.S. food industry sits somewhere on a learning curve in the early stages of Blockchain. During his opening keynote for the 2019 Blockchain for Food and Beverage event in San Francisco, Bob Wolpert, Golden State Foods’ Corporate Senior Vice President, stated that “Nobody is going to trust Blockchain in the beginning…If you cannot define how the customer will benefit, then you cannot identify the business value.”

Consumers will ultimately pay higher prices for food from a company that uses Blockchain. The industry promises for improved food safety are easy for consumers to buy into—especially when they have no idea how complicated the initial implementation is perceived at this time. This mountain to climb, in order to have Blockchain up and running smoothly throughout the entire industry as intended, is not lost on industry leaders.

One way of looking at the challenge of Blockchain is that this will require a fundamental shift in how companies deal with their data and what their competition, as well as their customers, see.

To learn more about developing trends in regulatory affairs, and how you can prepare to meet emerging industry demands, download our free guide below.

Related Articles

4 Ways to Stay Competitive in Regulatory Affairs

Emerging Trends in Regulatory Affairs in 2022

How to Stay Updated on Regulatory Changes